|

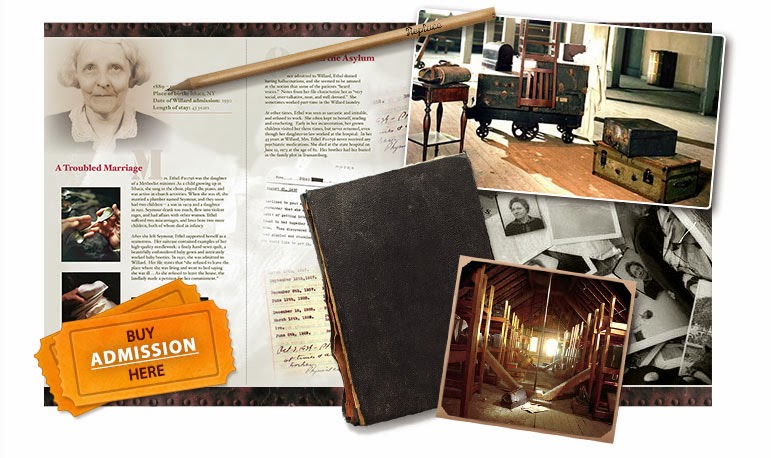

| Sketch of the Erie County Poorhouse by Robert Higgins |

I have been collecting data from the reports of the Medical Department of the Erie County Hospital (1880-1910) for the last several months for a scholarly paper I am writing. The hospital was part of the almshouse complex and so these reports were contained in the Report of the Keeper of the Erie County Almshouse in the Proceedings of the Erie County Board of Supervisors (available at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library). I've found that I have fallen into yet another rabbit hole! The Keeper's Reports are absolutely fascinating. In addition to vital and demographic statistics, they contain detailed inventories of every single item made, purchased or otherwise obtained for the care of the inmates and the support staff who lived on site. These reports provide a glimpse of life at the poorhouse, particularly at the turn of the century when they contained the most detail.

The inventories become more inclusive through time. Looking at the report from 1900, the enormity of the facility becomes apparent. Supply rooms documented thousands of pounds of meat, produce and dry goods. Hundreds of sheets, pillow slips, items of clothing and even funeral shrouds were listed in the various storage rooms. Kitchens housed piles of dishes, flatware, pots and pans. High end items, like an ice cream freezer, were noted in the Keeper's private kitchen.

In addition to the Keeper's quarters, there were private sleeping chambers for the Matron, physicians, and attendants. The 1900 Report also documented a Firemen's Room with furniture enough for two occupants. Fire was a persistent problem at the Erie County Poorhouse throughout its ninety-seven year history and the reports often indicated precautions taken to reduce that risk.

The various inventories provide some insight into how life at the poorhouse was organized. Administrative space included an office, a private office, and a reception room. The carpet, furniture and wall hangings were noted for each space, along with equipment and supplies. The Keeper had private quarters for himself and his family, including a separate kitchen, laundry, cellar and garret. The inmates quarters, clothing storage, washrooms and dining areas were segregated by sex. There was also a Old Ladies' Dining Room, an Old Men's Dining Room, and a Workingmen's Dining Room. The dining areas for elderly inmates had tables and chairs, whereas the dining room for able bodied working men had tables and benches.

Institutions of the nineteenth and early twentieth century were designed to be self sufficient, many were working farms. Barns and storerooms contained livestock, equipment and stores of produce grown on the farm. The 1907 Report listed 115 tons of hay and 16,000 heads of cabbage among its bounty. There was a bakery, a tailor shop, a boot and shoe room, a barber shop, a carpentry and paint shop and a lamp and oil room. There was even a Religious Services Room with a pulpit, an organ, bibles, hymnals, benches and chairs.

On the surface, it seems as though the almshouse had adequate facilities to care for Buffalo's institutionalized poor. Certainly there were times when the facilities were over crowded and had fallen into disrepair. There were often discussions in these reports of the need to replace or repair different parts of the poorhouse, insane asylum, or hospital. Early reports indicated times when the quantity of food was not adequate. However, it must be remembered that individuals who chose to seek refuge there or were sent there by the authorities, had no other options and might have died from starvation, disease or exposure if they had not found their way to the poorhouse.